Opscidia: Fighting Fake News via Open Access

In recent years, fake news has become a growing problem in the international information landscape. More and more projects deal with how to expose and avoid them. One of them is the project of Charles Letaillieur and Sylvain Massip. With a tool for the general public, the two want to support checking simple messages for their truthfulness with the help of open access publications and of artificial intelligence.

we were talking to Charles Letaillieur

A year ago, Charles Letaillieur and Sylvain Massip founded Opscidia, a free, open source and open access publishing platform hosting academic journals. Their intuition is that Open Access to scholarly articles will develop provided that applications can be found to reach a broader audience. Fighting scientific fake news is one of the applications they foresee. To do this, they use machine learning methods, process natural language and use a special text-mining pipeline. Based on Open Access publications, they have developed a tool that can determine the probability of a statement being true or false. In our interview, Charles tells us how this works exactly, and what potential he sees in the project.

Your project is about illustrating the possible uses of Open Access outside of academia. Why is this so important?

At Opscidia, we believe that the more applications to Open Science and Open Access, the more, and the quicker they will develop and become universal.

As soon as economic actors, public sector leaders and the general public will start using heavily Open Access to academic literature, the funding of publications will become easier and solutions will emerge.

Furthermore, we believe that Open Science is not just a philosophical objective, we want it to be useful to people and to society. To achieve that, applications need to be built to help reuse the knowledge shared in academic articles.

How can Open Access publishing combined with the right machine learning tools help to recognise and fight fake news?

Whatever your preconceived opinion about a scientific subject is, you will be able to find an expert (that is someone with academic credentials) and a few academic articles to reinforce your preconception. This will even be true, if you don’t cherry pick on purpose. This is the weakness of a search engine like Google Scholar, whose aim is to choose the most relevant article for you.

The Corona crisis has given very clear examples of this, with experts fighting on every subject, from the potential seriousness of the Corona pandemic to the usage of the mask. At the same time, the fights about the chloroquine articles and the “lancet gate” have shown yet again, that one single paper is never enough to end a debate.

Hence, in order to have a clear idea of the state of science, the only way is to analyse several articles on a given topic. But this is a long process and it requires research skills and a relatively deep expertise on the subject under study.

We believe that artificial intelligence can assist the public in this process. Our idea is to let the algorithms “read” this literature and sum it up for the user.

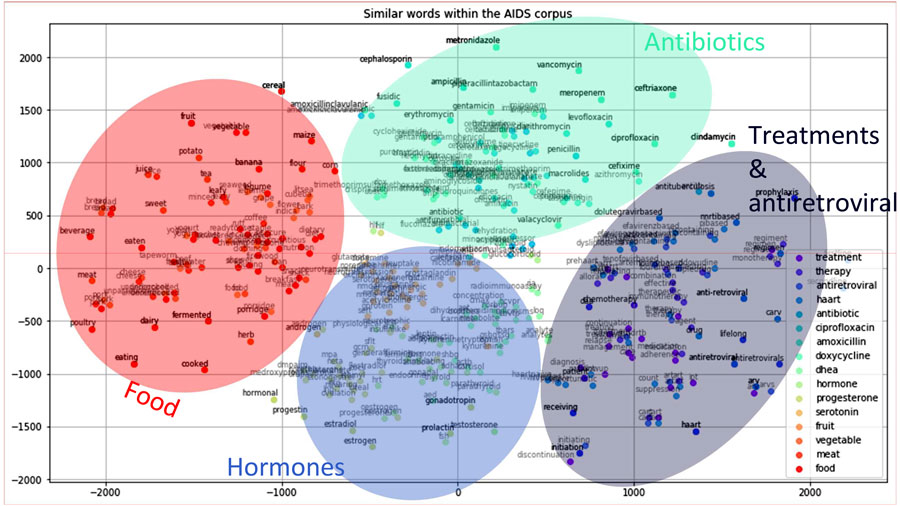

Is it really possible to build a text-mining pipeline that indicates whether a scientific claim is backed by the scientific literature? How?

We strongly believe that there is value in exploiting large volume of scientific texts, provided that every item reaches a sufficient level of quality, meaning that it is peer-reviewed published research. This is one of Opscidia’s main intuition: there is a lot of good research, which is not exploited enough because it is not findable. Hence, analysing a full corpus adds value to the simple consultation of the most distinguished experts. This project was originally inspired by the experience of a scientific journalist for whom finding the right expert for a given investigation is often very time consuming. Our Science Checker project is just a first step to help journalists like him!

On the fake science detection issue, our approach should be seen as a complement to the consultation of experts, because the expert-only approach has limitations. It is known that people can always find very distinguished experts with many credentials that are comforting their prejudices. For example, a French physiology Nobel Prize winner is claiming that vaccines are harmful. But these experts are always a minority. This is why it is indeed important to be able to listen to the whole community.

There are also historical examples to support this belief: at the start of Wikipedia, people really believed that it would never be any good, or at least that it could never compete in terms of quality with the traditional encyclopedia, written by experts. Now, it is recognised that it can at least compete with, for example, Encyclopædia Britannica.

We want to build a tool that helps people analyse the scientific literature that they don’t have the time to read. That is, of course, slightly different from telling them the truth!

Our approach is to build different indicators that will assist the user in getting an accurate idea of the scientific consensus on a specific question. Our objective is to indicate clearly to the user whether our analysis shows that the claim is backed, under debate or rejected by the scientific literature and to give them an evaluation of the level of confidence of this claim.

Where do you see limitations in this approach?

There are, of course, limitations to this approach: first of all, many issues are under debate with many experts on both sides. Our role, of course, is not to settle such debates.

Then, indeed, for a very specific claim, it may happen that there are not many articles on the topic. Our approach is statistical, hence, it is more error-prone if performed on a small number of articles.

The complexity of the claim also impacts the difficulty of the problem, that is why at first, we will only focus on simple claims of the form: Does XXX causes/cure/prevent YYY.

How can libraries support your projects or similar ones?

By helping to develop Open Access publishing. There is a need for high quality venues for Open Access publishing. We are running one at journals.opscidia.com. There are many others. As said earlier, Open Access publishing and its applications have to be developed hand in hand.

We understood that the target group of the text-mining pipeline is the public. Would it also be interesting for researchers? If so, at what point in their research process?

Yes, it is indeed designed for the general public. Nevertheless, it could be useful for a researcher who tries to understand the basics of a new field for a transdisciplinary project for example. Furthermore, scientists are also citizens, and they could be interested in checking claims that do not relate directly to their research but on which they have personal interest.

What would happen if your system discovers fake news? How transparent are the reasons for this decision to the user?

Our system is conceived as a decision support tool. It is here to help the users, but does not decide instead of them. Hence, the evaluation of our system has to be very transparent, and we will make sure that we explain clearly how the results are established.

The result of each indicator will be displayed and there will be a user guide that will explain the indicators and why we think they make sense. Finally, there will be links to articles in order for the user to be able to check by themselves if they wish to.

Do you plan to develop an automatic fact-checking tool or an online application yourself? When?

Yes, absolutely. Our poster“Leveraging Open Access

publishing to fight fake news”at the Open Science conference 2020 was a brief proof of concept.

We have recently obtained a grant from the Vietsch Foundation to build a prototype.

In this first version, three indicators will be built, to answer the following questions:

- What are the sources? Has the claim been studied for a long time? Is it still live? Is it widely studied in many institutions in many countries?

- Is the claim likely according to a broad analysis of topic-related articles?

- Is the claim numerically backed by a number of articles?

To limit the scope of the project, this first version of the search engine will be focussed on health subjects and based on pre-designed questions. A mock-up website for the project is available. It exhibits examples of the kind of indicators that we will see in the final version of the project.

Would it be possible to extend your approach, for example, by recognising open research data attached to the publication?

There will be several ways to extend our approach beyond this prototype. First, by adding new sources. We will start working with Europe PubMed. Second, by allowing more complex claims than the ones that we are developing for our prototype.

Indeed, looking at other media such as Open Research data would be another great improvement. We will certainly have a look at it at some point, but first, we will put our focus on articles.

Charles Letaillieur is a web and tech professional with 12+ years experience in crafting disruptive products around Open movements (OpenData, OpenGov). About 1 year ago, he co-founded Opscidia with Sylvain Massip. Their goal is to improve science using artificial intelligence and Open Access publishing.

The copyright of the photos belongs to Ralf Rebmann, Chloé Lafortune and Charles Letaillieur.

View Comments

Open Science Training: How to Implement Methods and Practices in European Research Libraries

How can the principles of Open Science be implemented in European research libraries...